Sources as Fundamental Pillars of Science

Dr. Oleg Maltsev

Academician of Ukrainian Academy of Sciences.

Founder and director of The Memory Institute, Head of the Expeditionary Corps.

Source Criticism/Source Studies — discipline, responsible for the description

and classification of historical sources.

Ushakov’s Explanatory Dictionary (D.N. Ushakov, 1935-1940)

Today, in an age of rapidly advancing technology, information is pervasive. It is invisible, colorless, survives even in a vacuum, and operates literally in all spheres, spreading faster than any virus. Working with this substance is an essential and necessary skill for scientists or journalists and perhaps for every inhabitant of our planet. But it is not enough to have supersonic access to cloud repositories or libraries that have preserved the legacy of numerous generations before us. It is not enough. What is truly important is whether the information encountered daily is factual, regardless of one’s occupation, profession, preferences, beliefs or nationality.

IS IT TRUTHFUL WHAT HAS BEEN WRITTEN AND DECLARED?

The world of a scientist and the world of science differs from one another in particular requirements. A researcher cannot work with information only because it has “come into his possession.” It is not advisable to rely on any source as the ultimate truth either. The requirements for a scientist are different; he or she must be able to analyze and justify, reason and present valid results of his scientific activities. This paper reflects a brief scientific intelligence work narrated in a popular science style-focused on contemporary problems in source studies as a methodological section of academic work.

Today academia is dominated by generally accepted statements and stereotypes that humankind has ‘stepped forward into a bright future of progress and technical excellence,’ primarily compared to ‘uneducated predecessors’ who existed 300-500 years ago. ‘Is that true?’ remains an open question. But certainly, it is not realistic to conclude that modern science is victorious daily and flourishes with discoveries and steady evolution. On the contrary, the opposite trend is more common, which indicates stagnation. In terms of methodological discourse on the quality of scientific results in the 21st century, a vital aspect of the scientific foundation is evaluation and studying sources.

Young researchers are introduced to source criticism and the significance of the given skill. Speaking of written sources such as books, monographs, brochures, scientific publications, all of them should be accurately positioned according to their rank, qualitatively strengthening and, most importantly, verifying the conducted research, authenticating the soundness of judgments and the relevance of research outcomes. However, with the preponderance of information technology and inclusive digitalization, the very essence of scientific knowledge—source studies—have undergone abnormal mutations and simulation. Fake sources, the implicit customary way that does not require verification of data source, business projects that scientifically justify things that do not exist, among many other things, is becoming a negative tendency.

The question is, does “referencing to a source” equals the “quality of that source”? What if a long-established source is an example of inaccurate information? There is a current bizarre trend implicitly, which implies that a written source is a source that definitely should be used and referred to in the research. Does it even matter if it was an intentional misrepresentation or the outcome of a theoretical project that has nothing to do with reality?

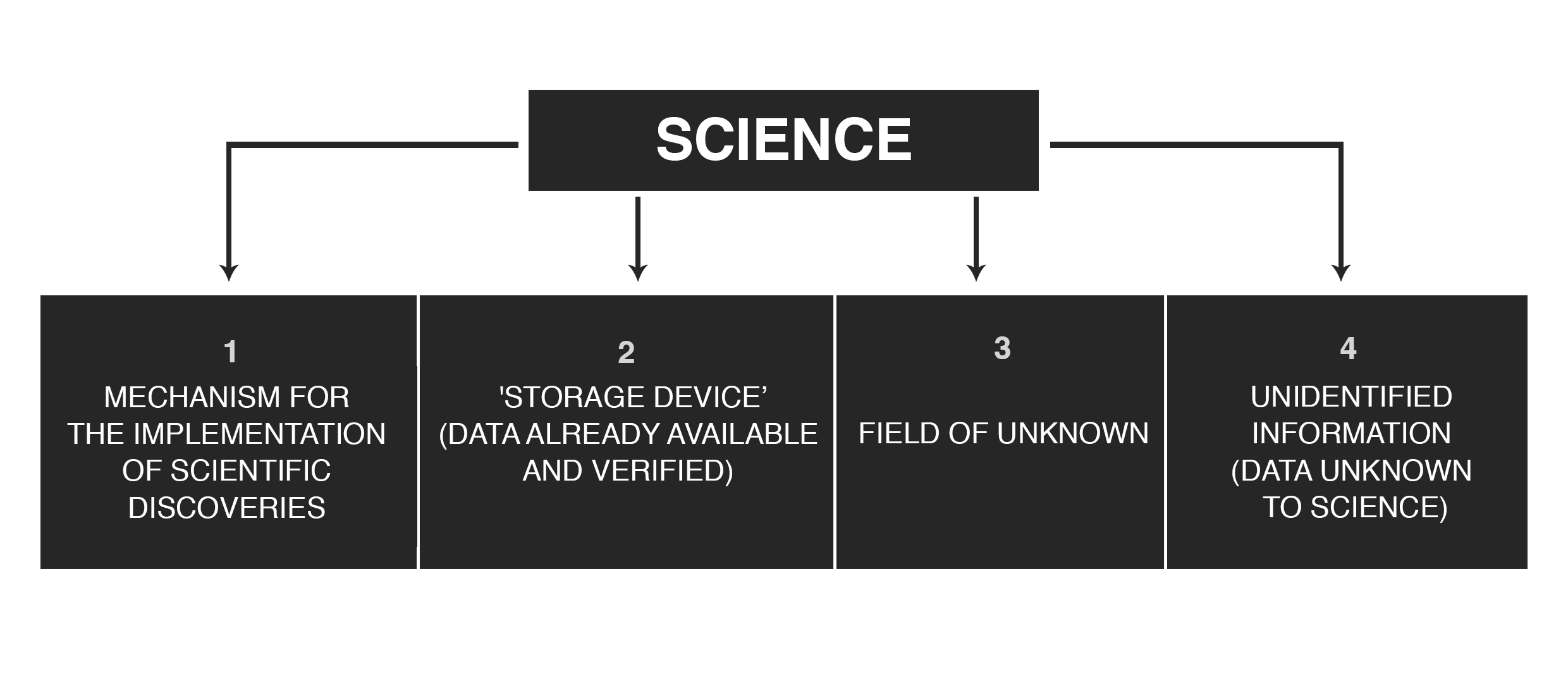

Before opposing or refuting the relevance of the questions mentioned above, it is suggested to go back to the starting point, science itself as a system. The following heuristic model is suggested for the discussion; consider science as a system shaped by four interconnected blocks:

- Mechanisms that allow making scientific discoveries;

- The block nominally termed the ‘Storage device’ (for previously available and verified data)

- Field of unknown—what remains to be explored, the environment that necessitates being discovered and researched;

- Unidentified information (unknown data to science)

According to the given model, we could conclude that current academic science is faced with at least four global challenges.

Challenge Block #1 is directly associated with the mechanisms of scientific research. Including every mechanism, technique, procedure, programme, approach, test—everything that allows us to create science as such and it’s legacy. However, the most common situation is that modern researchers are not aware of what mechanisms they could use (practically no institute or scientific circle shares knowledge as such). More importantly, they do not even question the validity of their research methods and tests.

Validity means reliability. Verified reliability is a problematic parameter # 1. For some reason, there is a focus on specific stereotypical “it is customary,” “everyone does this,” “it doesn’t matter whether this test is unreliable; it has been practiced for 50 years,” and so on. But the truth is that useless thing will prove their ineffectiveness in the next 50 years as well. If there are errors in calculations today, tomorrow will be a failure. The assumption that “everybody has been using it for a long time” is not constructive and does not allow us to achieve reliable scientific results and products, technologies as a consequence.

Challenge Block #2. The idea is to conceptualize the so-called ‘storage unit’; databases and other information blocks constitute a specific environment. The environment is neutral by its nature; it does not possess qualitative characteristics as “good or bad.” Characteristics are imposed by an individual who perceives or shapes his mindset through the prism of his beliefs. The so-called ‘prism’ is no longer objective as the interaction of different views shapes it. The scientist also has his own set of opinions and ideas — autonomous clichés and tenets that could be historical, social, cultural, psychological or even irrational.

The tenets classify what is being perceived as ‘correct,’ ‘acceptable,’ ‘mainstream,’ which affects the scholar deciding the course and the results of his scientific work directly.

Arguably the most significant problem with the ‘storage unit’ is the problem of sources objectivity. I will not even classify how any data (scientific, among others) gets manipulated to produce an ‘information substance’ in a storage unit that is ‘convenient’ for specific projects these days. Besides, some data becomes outdated and no longer relevant over time, and, of course, such data has to be ‘removed’ by the formatting of a ‘storage unit’ just like a hard drive on our computers.

Challenge Block #3. The unknown field conceals its ‘threats,’ be it the ‘impassable depths of ignorance’ or the ‘black holes of misunderstanding.’ Metaphors aside, the main problem of ‘unknown fields’ is that scholars do not possess any tools to explore them. There is no validated methodology or approach, allowing one to research the unknown, besides those repeatedly applied without any result. The introduction of a new method or instrument today is perceived as an incredible scientific achievement. The aforementioned is not because there are very few worthy methodologists, but because the procedure has been elevated to the level of an almost insurmountable test that might take a life-long period. Conversely, there is an extensive library of non-functional methods in certain disciplines, but they are considered acceptable and functional.

Challenge Block #4. Data unknown to science. First, some data seems to be known to science. They are regarded as known, but in reality, no one understands ‘how it works’ and does not talk about it out loud. Secondly, very often, certain information is misleading for political, economic or sociocultural reasons. It is not clear how to apply or use it despite the presence of a phenomenon. Finally, the easiest but honestly ‘dead-end question’: how exactly is one supposed to explore something unknown? What if no one is aware of it? And even if there are assumptions, one is required to:

A) refer to other researchers who never studied that field;

B) demonstrate that there is something different—it could be very complicated because of the risk of shattering the already established information environment used for manipulation. It is not even a matter of research tools nor a lack of ideas. The fact is that 90% of discoveries today are carried out either by accident or intentionally. For instance, after the Italian Republic’s emergence in 1862, a new political circle required heroes to confirm the Italian identity. Almost “magically,” those heroes and Italian “ancient” books made their appearance. In one way or another, science relies on sources, and it depends on how the scholar will use those sources (provided he has proper functional methods, technologies, approaches), as well as the quality of those sources.

The quality of the source requires close attention. Source study is an essential part of professional activity these days that relate not only to scholars. Whenever someone uses a piece of information without giving it a thought, it brings adverse consequences. Everyone with no exceptions can explore or study something. However, a scientist differs from an expert in any other field by one classification parameter: the ability to verify and confirm specific information using tools.

One of the powerful and objective tools in 21st-century science is photography. Yes, photography, which is often treated inattentively and even arrogantly, most likely because young people are simply pampered by technological progress. Yet this is not a matter of pressing the shutter release and automatically making a picture on a digital camera, but the idea of photography as a source of scientific information and a tool for conducting research.

Source study is one of the pillars of science which advances together with it. Handling documentary sources is quite familiar to the scientist, which is not the case when it comes to photography. The potential of the former is underestimated by many researchers today. While considering photography in the research, it is relevant to point out three functions inherent to it:

- Source of information

- Object of study and substantiation of hypothesis

- Source of scientific evidence

In the first stage of the research, photos are a source of information for the researcher. It is only one type of source of information among many others, but the most reliable one. It is prevalent to neglect this source in the first stage of the study, particularly in humanities. What is unique about photography is that it reflects the factual state of affairs at the given moment. They may help us to navigate in a particular period of history under study. Whenever I begin a study at the institute with my colleagues, we try to get as many photographs on the subject as possible. This approach is particularly useful in obtaining valid information when we cannot physically visit a place, which has existed, for example, in the past. We can’t go back in time, but photographs carry us back to those times.

Undoubtedly, there are written sources of information that reflect what had happened in the past, but they do not convey meaning as an image does. When we are reading a written document, we have to picture that image in our minds. This is how our perception system works; when we hear or read a word, let’s say “a car”, we immediately have a certain image of a car in our mind. Correspondingly, when a person reads a document, he makes up images in his mind in the way he wants. Sources such as engravings, paintings, frescoes and similar things would be useful when working with written documents.

In terms of credibility, certainly, photography is more reliable than a painting. It is often hard to determine the exact date of a painting or fresco in the temple. It could be two hundred years old or ten years old (re-created ten years ago during restoration). It is impossible to ascertain whether it repeats the original piece if there is no originals’ phototype. For instance, a scientist reading a written document shapes the image according to his reasoning but that image will not be original.

Consequently, a scholar initiates reasoning on the grounds of this naturally’ fabricated image,’ concludes and, as a result, does not acquire reliable data. It is helpful to recognize that each person represents the same subject, phenomenon and event uniquely and differently. Thus, we cannot consider our own and someone else’s ideas to be reliable. Suppose there is no photograph or sketch on the paper (written document). In that case, we cannot be confident that ‘it’ (the subject) looked like ‘this.’ This way, humanity’s entire history is divided into the before photography era and the photography era.

As a result of eight years of applied expeditionary research, a comprehensive methodology was developed and validated at the Expeditionary Corps (specialized department of the Memory Institute). The methodology provides scientists, researchers, and experts of various fields the skill of working with photography as a source of scientific evidence on their own. The methodological provisions are logical foundations that can set up a system of expert training, improve one’s skills, and be a training program.

An extensive research practice preceded the introduction of photography as a source of credible scientific data methodology. In 2012-2020, the author of this paper, head of the Expeditionary Corps, developed several key prerequisites of this approach and conducted its approbation in scientific projects, expeditionary studies, field studies, etc. Particularly in the period from 2015 to 2019, an expeditionary group consisting of experts in philosophy, psychology, anthropology, sociology and criminology, had a chance to independently examine and verify the reliability and quality of this methodology, researching the various phenomena of history in Europe (Germany, Spain, Greece, Italy, Czech Republic, Croatia), North America (USA, Mexico) and South Africa.

To learn more about the development of the methodology, its application and practical recommendations, please see the monograph “Photography as a Source of Scientific Information.”